by Matthew Cobb

The class Insecta contains many weird animals, although the weirdness lays mainly in the eye of the human beholder. Readers from the Americas who spent their childhood messing about by rivers will probably be no stranger to the dobsonfly, but to us effete types from elsewhere in the world, it is a bizarre beast:

(I don’t know where this image originally came from, and a Google image search didn’t help.)

Dobsonflies are not flies (order Diptera) – according to timetree.org they separated about 300 million years ago, not very long (in geological terms) after those crazy crustaceans came out of the sea and turned into what we now call insects. Dobsonflies are members of the order Megaloptera. This group used to be part of the Neuroptera along with lacewings, owlflies and antlions, but the order has now been split into the Megaloptera (dobsonflies, fishflies and alderflies) and the Neuropterida (lacewings etc). There are about 220 species of dobsonfly and about 300 species of megalopteran.

The larvae – known in the US hellgrammites and often used as bait by anglers – live in freshwater and take several years to develop. The dramatic and scary-looking adults emerge, mate and then die. Here’s some pictures of dobsonfly courtship and mating (quite SFW). They won’t hurt you, no matter how intimidating those mandibles look.

(Note the three occeli on the top of the head, just behind the roots of the antennae – these simple eyes are used for navigation (they detect polarised light) and also for rapid detection of movement overhead, and are shared by most flying insects – they are one feature that distinguishes queen ants (which have to fly) from their sisters, which do not.)

The dobsonfly in the picture above is an adult male; there is a sexual dimorphism, which strongly suggests either the males use those mandibles to tussle with each other for access to mates (like the mandibles of a stag beetle) or the females directly choose males with bigger/stronger mandibles. The antennae are also dimorphic, suggesting the males may track female pheromones:

Male (left) and female eastern dobsonfly Corydalus cornutus (photo by Lyle J Buss, University of Florida).

Here’s a nice video of a male crawling all over someone’s hand – the male tries to fly and you can see his two pairs of wings quite clearly:

The male also ‘pees’ on the man in the video – whether this is some kind of defence mechanism I’m not sure.

Females lay eggs on leaves above water, as a white mass. Females will often lay eggs on adjacent leaves, suggesting their may be some kind of oviposition pheromones. The larvae hatch and then drop into the water where they are ferocious predators, growing up to 9 cm in length and living under stones:

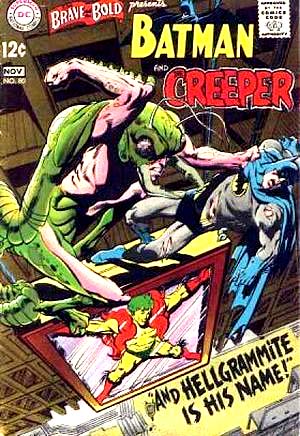

Hellgrammite from here. The name was even used as a supervillian in DC comics!

When the larva is ready to pupate (this can take five years), it migrates out of the water and its cuticle hardens to form a pupal case. The male’s long antennae are bent back, as this dissection shows (photo by Atilano Contreras-Ramos):

The adults then mate, and the whole cycle begins again.

Like mayflies and many other river-dwelling insects, dobsonflies are very sensitive to pollution. If you have dobsonflies in your local stream, be pleased! It’s a good sign.

One thing I haven’t found out – why are they called dobsonflies?

To find out more:

http://www.tolweb.org/Corydalus

http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/eastern_dobsonfly.htm

I seriously considered dropping out of college the first time I saw one of these while strolling across campus one evening (upstate NY). Back then, I was very phobic about insects, and had never imagined such a thing as this could exist!

I hope they are in the streams around where I live. I have a nice stream where on my property but it’s a bother to get to (down hill which means going up hill coming back)& often the tall grass is populated by the largest yellow orb weaver spiders I’ve ever seen. Once I discovered them in a panic, I never went back down there.

I suspect these flies could live in the stream though. I’d love to see them.

The yellow orb weavers are possibly ‘Argiopes’ of some kind. Please do not be afraid. They are the nicest, gentlest spiders. See for example a recent posting from Bug Girl. Like I say there in the comments, they just do not bite (well, I never have been, and I definitely used to ‘push’ it)! They might trigger some arachnophobia buttons, but they are really very nice. And pretty.

I understand they are not harmful & cannot bite. I also appreciate their prettiness but they trigger a strong, irrational arachnophobic reaction in me that sets me in a panic so they can stay on their side of the field & I’ll stay on mine. 🙂

Start with little jumping spiders (for maximum squee value), and work your way up? Its like judging dogs. Pit bulls look scary (and some are), but when you get to know a socialized one you discover that all they want is to be loved.

Hi Mark:

We (on this website) have been helping Diana work through her arachnophobia. She’s doing well ;-). Good pointers.

I live in a concrete jungle, and would pay well to see some interesting spiders (It’s not quite the same on YouTube). I suspect that all the plants around where I work and live are sprayed regularly; except for ants, I don’t see much in the way of invertebrates at all 🙁

Ha ha yes I like jumping spiders. I appreciate spiders and like to learn about them. They Are very old and that body type seems to have worked for them all these years. There are even ones that mimic ants. I also live with those skinny ones throughout my house and save them from the bath tub though they do occasionally cannibalize one another; such is the way with spiders.

Hey look, there are even entomologists who are afraid of spiders! Now I don’t feel so bad!

What a ferocious but docile looking animal! I have never heard of these flies but now I wish we had them where I live. The eyes on the top of the head are brilliant & I can’t help but to compare them with the various machinery humans have made with sensors all over (quadcopters, roombas).

I saw something that looked a bit like the larva smashed on my son’s driveway. It was shiny black on each section like the first two sections in the photo. The legs where yellow and it had a bit of red at one end and a bit of yellow at the other. It was long, maybe 4 or 5 inches. My grandson (21 months) and I inspected it for quite a while.

I wish I had taken a picture. Does anyone recognize the description?

Sounds like a scolopendrid centipede; here’s one that seems to match colour-wise, but there’s probably a similar species wherever you live.

Thanks for pointing me in the right direction. I think the insect we saw was a scolopendra heros. I live in Texas hill country.

In the midwest where I grew up fishing with my grandfather, we used “hellgrammites” to refer only to dragonfly and damselfly larvae. But then, I don’t think we ever came across a larva of a Dobsonfly to test the limits of the term.

Thanks for that – what an AMAZING creature!

I would struggle to stay calm with it crawling all over me!

From bugguide.net: “The word “dobson” sounds like a folk etymology for another word foreign to English speakers. Possibly the origin is a Native American word for the larva. Another possibility is that it is a reference to another aquatic creature, the dolphin (from French daulphin, see Wikipedia–Dolphin, Online Etymology Dictionary–dolphin). Note that originally “dobson” was a term for the larva.”

Ha! You beat me to it but, I haz the secret weapon. A link to the bugguide remarks subheading for Corydalus cornutus – Eastern Dobsonfly

In one of my former lives I used to collect these at lights near Flagstaff Arizona. They were of interest to me b/c in many ways they are very ‘primitive’ in their anatomy. I soon discovered that certain streams were full of their larvae. Those huge larvae looked terrifying, like giant centipedes, but fortunately that particular species could not bite. Their pinchy looking jaws could only tickle. Based on their gut contents I concluded that they were scraping up algae from rocks. Btw, all those extra leg-like appendages in the larva are gills/sensory organs.

Keep the arthropod posts coming!

While it’s true the males can’t inflict any harm with their oversize mandibles, the females can give you a pretty good pinch with theirs. We have quite a lot of these where I live, they often are attracted to lights at night. The areas where you can find the larvae here are very clean, fast flowing and rocky. They can be found in between and under the stones.

I at first thought this article would be about “Dr. Dobson” of odious “Focus on the Family” notoriety. I am very pleased to find that I was mistaken, but I feel sorry for these remarkable creatures that they share a name with such a lower form of life as that radio evangelist.

Beat me to it. I was going to say that we have a big Dobsonfly right here in Colorado Springs… except it isn’t nearly as pretty.

Holy smokes! Mega indeed. I have never seen such a creature, but would really like to.

Perfect for a low budget cheesey monster flick. Deadly poisonous, man eating MEGALOPTERA

My kids will love these things.

Tell them this is what breakfast will consist of if the do not behave!

😉

…or, rather, that they’ll have to fight with one for breakfast, with the loser being dubbed, “breakfast”….

b&

Hah! That would certainly backfire. Then I would have to find some of these things to feed them for breakfast.

They know every critter within a mile of our home on a first name basis. From bug to bird, to spider and snake. I’ve been woken from a sound sleep more than once with something thrust in my face from one of their early morning expeditions. For example a five foot, pissed off snake.

First, I’d like to thank Matthew Cobb for keeping the website active during Jerry’s perigrinations and book writing.

I don’t have dobsonflies in my creek. It’s the wrong habitat — no rocks to speak of. I think they prefer what anglers call freestone creeks instead of spring creeks. I have have abundant mayflies of several species, though, and lots of damselflies and dragonflies and midges.

Wow! And they tell me Australia has all the terrifying animals! Though if it’s as harmless as you say I guess it wouldn’t fit in.

Those Megaloptera are named “machacas” in Colombia. There is a related myth with them:

If a “machaca” bites you, you “must” have sex in the next 24 h unless you want to die.

Keep it in mind when visit Colombia.

No, that is something completely different, a kind of giant planthopper.

Hi Lou, you’re right

Lots of my Amazon friends really believe the part about having sex within 24 hrs…or at least they say they believe it…..

Reblogged this on Mark Solock Blog.

If the topic is large insects with strange life cycles, this is my favorite: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sphingidae

sub

This seems to be the original photo: http://www.pawild.net/home/gallery.php?photo_id=3858&p=view_photo

That’s according to this page: http://www.whatsthatbug.com/2011/01/30/male-dobsonfly-42/

When I was taking a tropical herpetology course in costa Rica, we’d find these in the camp at night. We’d exclaim this line from Jurassic Park (substituting ‘Dodgson’ with ‘dobson’.

http://m.youtube.com/watch?v=AERwgNvgMmc&desktop_uri=%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DAERwgNvgMmc