Although it’s really the second day since I arrived in Amsterdam, I didn’t do much yesterday because I was exhausted. So today, Monday, really counts as Day 1.

And oy, did I sleep last night! After chatting with my host and a few people connected with my visit, I took at nap at about 1 p.m., but was restive and woke up without much sleep at about 6 p.m. But then the serious sleeping began. I crashed at 7 p.m., woke up 5 hours later, at midnight, checked my email (there’s a seven-hour time difference from Chicago), and then went back to sleep, waking up totally refreshed at 5 a.m. I got at least ten hours of deep sleep, something unknown to me!

It was too early to make noise or disturb my hosts, so I crept downstairs—two flights of the steepest stairs I’ve ever seen in a house, for Dutch houses are high and narrow. There I found a copy of yesterday’s New York Times, a local map, and a note that there was Balinese food in the fridge from the nearby restaurant (rated one of the best Indonesian places in the city). What could be a better breakfast than Indonesian beef, green beans, other veggies, and chicken atop a bed of rice and heated in the microwave. I read the NYT as I dined, noticing that Bret Stephens’s column on the U.S.’s poor treatment of Israel was on the front page of the paper edition—something you wouldn’t find in the U.S. (column archived here).

While I finished my food and perused the Times, a wonderful event occurred: a beautiful fluffy and shiny black CAT wandered into the kitchen. In less than a minute we had made friends, and in 2 minutes he was on his back, allowing me to give him belly rubs. (I have a way with cats.) I later found out his name is Toom. Here he is:

As you see above, Toom soon jumped up on the sink and looked expectantly at the faucet. Could it be, I thought, that he wanted a drink? I turned on the faucet lightly, and Toom went to town. First he stuck his paw under the flow until it was wet, and then licked his paw.

Here is a video:

But then Toom put his back under the faucet, too, and then licked the water off his back! Granted, he did use his mouth to drink from the faucet, too, but preferred licking water off his back and paw.

The Back Lick:

After 90 minutes my host came downstairs, taught me how to make coffee with the machine, and we had a cup and chatted for an hour or so until she went to work. (I’m staying with a married couple, but the husband is on a work trip for a few days.)

Here’s Toom with a post-lick blep:

After breakfast I had a leisurely walk around the area (I’m staying in a lovely part of town, a half hour walk from the Museum District). My host had also having furnished me with a tram/bus/train pass, but I needed a morning constitutional.

I walked to the Museum area, hoping to get into the Van Gogh Museum, one of my favorite museums in the world. (I love the later van Goghs.)’d been told that you have to reserve tickets in advance, which I didn’t have to do the last two times I visited here, and, sure enough, when I showed up everyone had reserved tickets. I asked the guard how long I had to reserve in advance, and he replied “About two weeks.” Oy! But he added that if I went online right at 5 p.m., I may be able to get tickets for tomorrow. I’m not sure I’ll do that as there are things to see in Amsterdam that I haven’t seen twice before. (My first talk isn’t until Thursday.)

Once again the day was lovely: tee-shirt weather. You know you’re in Amsterdam because there are bicycles everywhere:

The obligatory bike-mirror selfie:

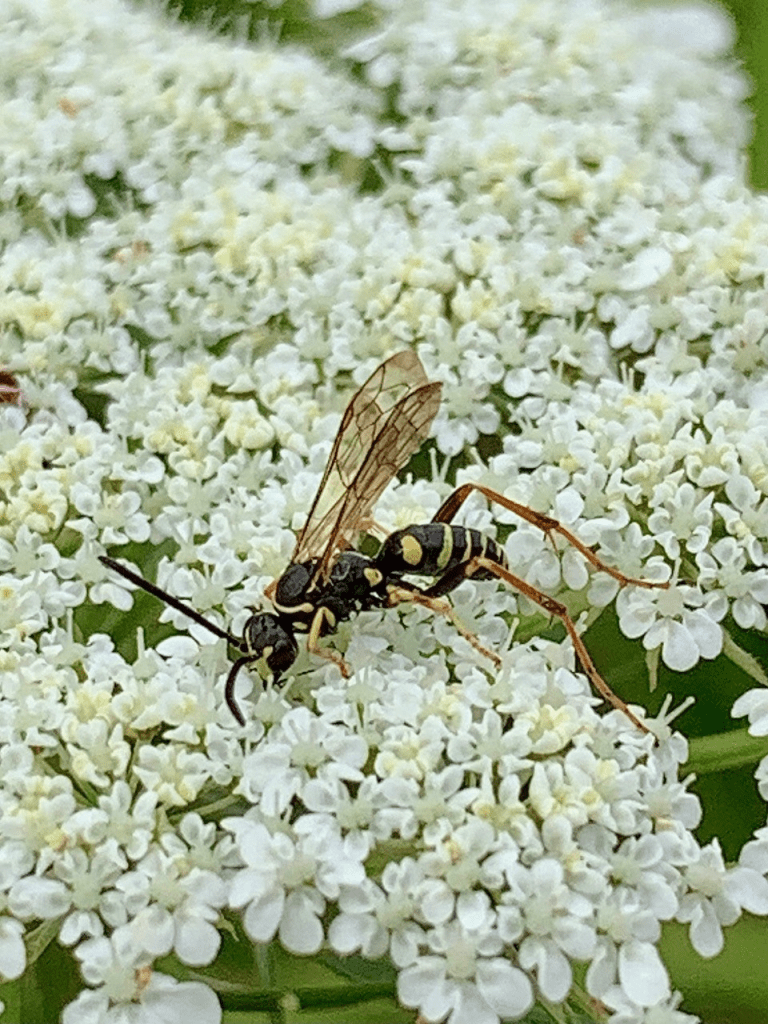

My best guess is that the denizen of Amsterdam below is a Western Jackdaw (Corvus monedula), but readers can help out.

This is the smallest car I’ve ever seen, and there are plenty of these in Amsterdam, as parking is quite difficult. It can hold two people in the one seat if you’re squashed up together.

I think it is a LuQi electric mini-car, which runs about 10,000 Euros. It may be made in China but I don’t have enough information.

You can fit them into a space only a few yards wide:

The interior. You better be friendly if you have a passenger.

While looking around the Museum Quarter, I found “The Best Hot Dogs in Town.” I can’t vouch for that, but I’m sure that a good Chicago dog, dragged through the garden, is way better.

Finally, I took the tram to the Central Station (it’s nearly a straight shot from where I live, with an intermediate stop at the museums, to fulfill a long-time craving: Dutch friets with thick mayonnaise. This, along with raw herring, is one of the two great street snacks of Amsterdam. I was last here a while back, but I remembered the location of a good friets stand near the station, and, sure enough, dead reckoning brought me to my goal:

That was lunch. And you needn’t tell me that it’s not the healthiest of foods, as I already know. I have tried the raw herring, but couldn’t abide the malodorous fish, and I’m not a piscivore anyway.

Now it’s time to rest a bit, work on my talk, and read the book I brought: Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant.